By Susan Riddell

susan.riddell@education.ky.gov

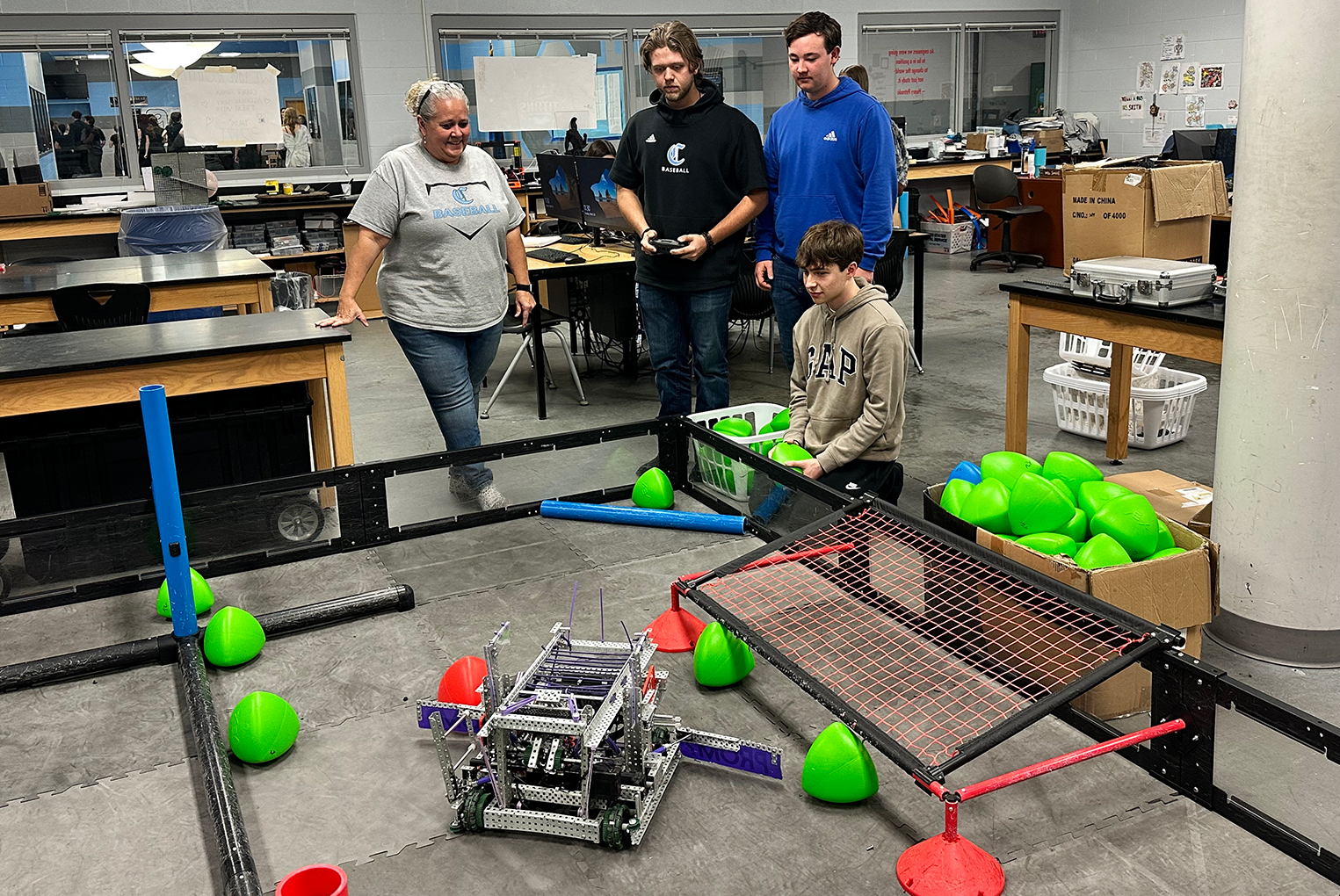

Western Hills High School (Franklin County) junior Nathan Eversole stands near the filtering system used to create biodiesel at the Franklin County Career and Technology Center. Photo by Amy Wallot, Jan. 30, 2012

When Francis Wheatley sees fuel prices go up, he’s not discouraged. Neither are his students.

“My students just have this feeling of self-reliance,” he said. “We don’t worry too much because we know there are alternatives out there.”

Wheatley is in his 17th year as the automotive teacher at the Franklin County Career and Technical Center (FCCTC). Throughout most of this school year, he and roughly 20 students have been making biodiesel fuel at the school.

“Right now, alternative fuels are a big deal,” Wheatley said. “We are playing a small part in it, but we all feel like we’ve got to do something.”

FCCTC began participating in the newly-formed Kentucky Biofuels for Schools program this past fall. The Kentucky Biofuels for Schools program is the result of a 2010 TogetherGreen Fellowship received by Kenya Stump, a Division of Compliance Assistance employee and creator of the Kentucky Biofuels for Schools program. TogetherGreen is an alliance between Toyota Motor Manufacturers and Audubon, the national conservation organization, to help develop conservation leaders.

“The purpose of the Biofuels for Schools program is to encourage Kentucky high schools to teach, produce and use biofuels within their schools and community,” Stump said.

Wheatley said it’s relatively simple to convert waste products into a reliable alternative fuel.

He and his students take used cooking oil from local restaurants and the Franklin County High School cafeteria. They filter the oil to remove large particles, store it in a tank and run it through a sock filter process.

“Then we do a little chemistry to see what chemicals need to be added to turn it into biodiesel,” Wheatley said.

The process takes about three to four hours to complete which translates into two to three days of class time, he said. So far, the students have made some 100 gallons of biodiesel. They use it for agriculture equipment, lanterns and more.

Glycerin is a byproduct of the conversion to biodiesel. Wheatley said the students are converting it into soap and candles. It is also an excellent degreaser that comes in handy in an automotive shop.

Wheatley said he would love to see the biodiesel eventually used in district school busses. If that caught on, districts could potentially save lots of money, he said.

Wheatley has been converting waste to alternative fuels on his own farm for six years. When he crunched the numbers over a year’s time, he went from spending $1,200 to just $70 spent using biofuels.

While saving money and producing an eco-friendly product are big advantages to this effort, student learning is another byproduct.

“Curriculum is easily adaptable to meet state science and math core content standards,” Stump said. “Teaching biofuels within the schools helps make science and math concept more accessible and presents real-world applications beyond those just in the lab or classroom. Students are actively engaged in problem-solving and teamwork on a daily basis.

“This program is a way to engage students who may not have had an interest before in science, math and engineering,” Stump added. “It gives them a glimpse of future educational opportunities and new careers. Biofuels education in schools is multi-disciplinary. It can reach automotive students, agriculture students, engineering students and business students, and it is a lightning rod to bring these students together by working on one single project.”

Kentucky is a positioned to be a leader in the biofuels industry, Stump said.

“Alternative fuels, specifically biofuels, are an integral part of Kentucky’s energy future,” she said. “A program like this helps prepare students for green job careers in Kentucky and, specifically, within the automotive sector.

“This program also exemplifies green chemistry principles in that you do not create any waste and everything is either used or reused for a purpose,” Stump added. “Students are understanding concepts such as energy conservation and pollution prevention. It is very powerful to take a waste product and turn it into a usable fuel. That lesson is transferable to many aspects of a student’s daily life.”

While the Franklin County Career and Technical Center is one of the early participants in the biofuels programs, others are jumping on board, Stump said.

“Kenton County has expressed an interest in biofuels education, and I know Lindsey Wilson College runs a summer program with the local high school that incorporates biodiesel education and production,” she said. “Fayette County’s new Locust Trace Ag Science Farm also is exploring biodiesel education within its new facility.”

FCCTC, meanwhile, will likely expand its program.

“We’re going to work with wood pulp to make wood gas fuel that will run an engine,” Wheatley said. “Next year, we’ll be dealing with solar options. There are all kinds of fuels in the transportation industry, and I want to keep my students thinking outside the box.”

MORE INFO…

Francis Wheatley, francis.wheatly@franklin.kyschools.us, (502) 695-6790

Kenya Stump, kenya.stump@ky.gov, (502) 564-0323

Leave A Comment