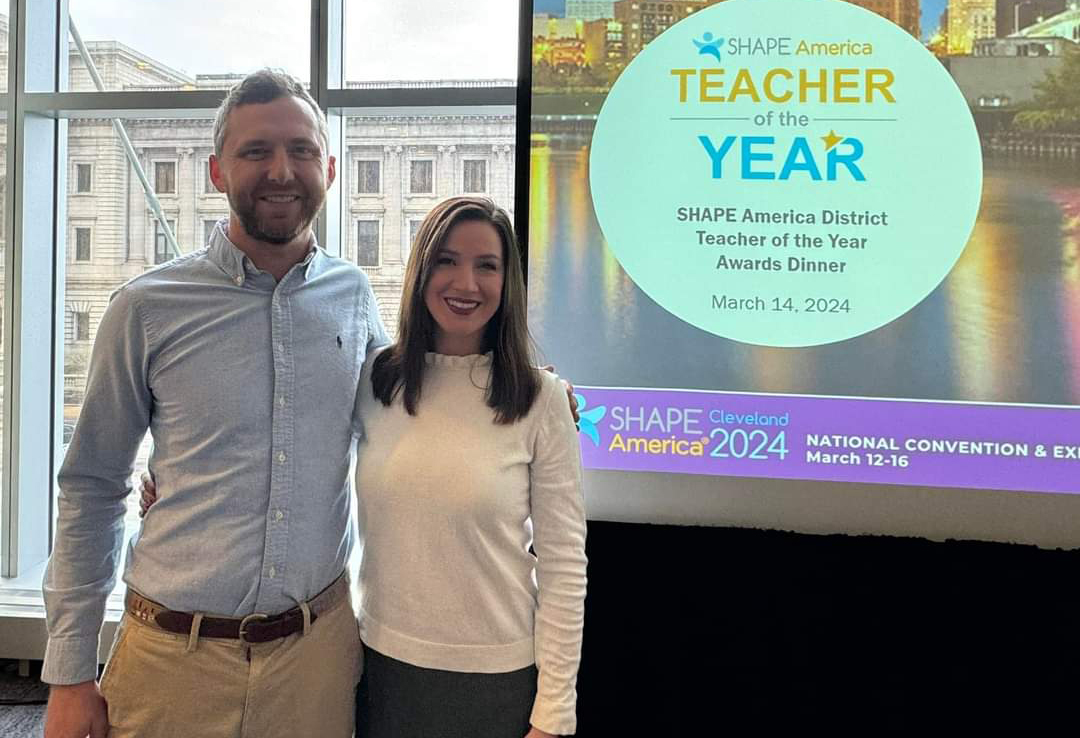

Archaeologist Randy Boedy tells how the shelter provided by the Natural Arch may have been used by past generations during Project Archaeology.

Photo by Amy Wallot, July 9, 2014

By Brenna R. Kelly

Brenna.kelly@education.ky.gov

This fall, students in Lynn Lockard’s 6th-grade social studies class will get to be nosy people. They will investigate dwellings to learn about how people lived in the past.

“When you think about people’s homes, you really can learn a lot about the people, their culture, their beliefs and what they are interested in,” said Lockard, a middle school social studies teacher at Barbourville City School (Barbourville Independent).

She was one of 14 teachers from the Lake Cumberland region who participated in a weeklong academy this summer designed to teach educators how to engage students by using inquiry-based instruction.

The academy, Making History Local: An Inquiry-based Approach, used the national Project Archaeology: Investigating Shelter curriculum, which focuses on shelter as a way to explore how people lived and uses archaeology as a tool for investigation.

“By looking at material objects and material culture, the archaeology project involves students in inquiring into their community and its connection to the rest of the world. It helps students learn something about that world,” said Linda Levstik, a professor in the University of Kentucky’s College of Education, which helped present the academy along with the Kentucky Archaeological Survey.

Using inquiry to teach social studies, particularly history, educators say, allows students to explore and interpret the past instead of being told what to think about it or just reading about it in a textbook.

“Because the students are being active learners, rather than being passively provided information, they learn more deeply, more completely,” said A. Gwynn Henderson, education coordinator for the Kentucky Archaeological Survey. “The kids are compelled to explore to find the answers to the questions, as nosy people, we want to find the answer.”

During the academy, which was funded by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Nashville District, the teachers visited Daniel Boone National Forest, where they explored two places people lived: a rock shelter near the Natural Arch where prehistoric people camped, and a cemetery still in use at the Barren Fork Coal Camp, a McCreary County coal company town abandoned after the mine closed in the mid-1930s.

At the arch, the teachers imagined living in the alcove near the 100-foot-long sandstone bridge and plotted where they would sleep, cook and throw their trash.

“I wish my students could be here and see this to make this connection about how early people lived and how their basic needs were still the same as we have today. We just go about it in a different way,” Lockard said. “I just think it’s such a teachable moment, and it really reinforces what it means to survive in a world no matter what the time period is.”

Lockard and three other teachers are piloting the curriculum this fall while many of the other academy participants will use pieces of the curriculum in their classes, Henderson said.

The curriculum, which is a science and social studies unit for grades 3 through 5, explores all aspects of shelter, from why people need shelter to how shelters reflect the people who built and used them. It also teaches students to use the tools of scientific and historical inquiry to study shelter and what the shelter can tell them about the people who lived there.

Investigating Shelter includes case studies on many different North American shelters, both historic and prehistoric. At the academy, teachers ended with a lesson based on a shotgun house in the Davis Bottom neighborhood of Lexington. That case study was part of the Davis Bottom History Preservation Project, a collaboration of scholars, educators and residents that documented the neighborhood before the construction of a road altered the area.

When the shotgun shelter lesson is taught in classrooms, students learn to become researchers, or “nosy people,” and use census records, fire insurance maps, oral histories and artifacts found during an archaeological excavation to understand the people who lived in Davis Bottom.

African-Americans settled the area, on the western edge of downtown Lexington, in the late 1800s. The integrated neighborhood of mostly shotgun houses also became home to working-class people from eastern Kentucky in the early 20th century.

“What we were looking at is how do we give a voice to people who might otherwise be silenced in the historical record,” said Levstik, who teaches in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction.

The curriculum also includes a stewardship component that gives students the tools to evaluate a cultural heritage and assess how important it is to preserve, Henderson said.

As a final performance of understanding, students role-play to apply what they have learned. At a mock city council meeting, students take positions as preservationists, archaeologists, developers, highway engineers, current residents and new families who want to move there.

“They must think about all those extenuating circumstances that surround real-life situations – it comes down to all the different people, groups, who have differing perspectives about what should be done with our heritage,” said Henderson, who is also an adjunct professor in the UK Department of Anthropology.

This inquiry-based instruction and having students apply what they have learned also fits with the College, Career and Civic Life Framework (C3), Henderson and Levstik said. The C3 Framework, which was used in developing the proposed social studies standards that will be considered by the Kentucky Board of Education in October, uses an inquiry arc that includes developing questions and planning inquiries, applying disciplinary tools and concepts, evaluating sources and using evidence, communicating conclusions and taking action.

“I really got excited because I am thinking this is more the direction social studies will be heading,” said Lockard, whose 6th-graders will use the curriculum for about 10 weeks. “This hopefully will give me a model for the future to use with the 7th– and 8th-grade students on how to make learning about history more engaging through inquiry.”

The curriculum itself and inquiry-based instruction in general are also supportive of the Kentucky Core Academic Standards because students are asked to read and write in a variety of genres, Levstik said.

Teachers can use the inquiry-based instruction and the research skills they learned by teaching Project Archaeology and apply it to other teaching and learning contexts in their classrooms, Henderson and Levstik said. They can even use the technique in other subject areas.

“Inquiry is not discipline-centric,” Henderson said. “Inquiry is all about coming up with a question and exploring, trying to figure out the answer, assessing, weighing the data, making observations, inferences, drawing conclusions and going from there.”

FOR MORE INFO…

A. Gwynn Henderson, aghend2@uky.edu

Linda Levstik, linda.levstik@uky.edu

Lynn Lockard, lynn.lockard@bville.kyschools.us

Leave A Comment