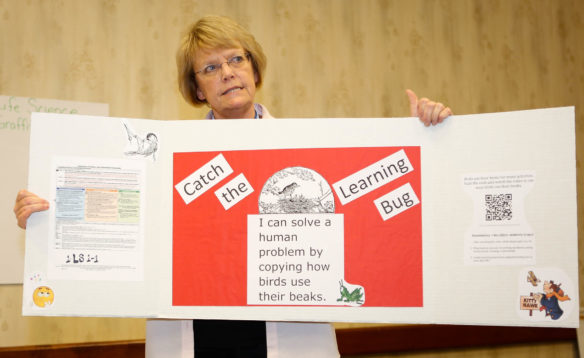

Vivian Bowles, a 4th-grade teacher at Kit Carson Elementary (Madison County), explains one of the pencil box science experiments at the Let’s TALK conference in Covington. The Kentucky Education Association developed the experiments to help elementary teachers implement the Kentucky Academic Standards for Science.

Photo by Brenna R. Kelly, June 13, 2016

By Brenna R. Kelly

Brenna.kelly@education.ky.gov

When Sharon Thompson-Saito asked a room full of elementary teachers to identify their biggest barrier to teaching science, she was met with one resounding answer: time.

“Science and social studies are at the end of our day because literacy and math are more of our focus,” said Amanda Hoskins, a kindergarten teacher at Lebanon Elementary (Bullitt County). “Not that science is not important, we try very hard to get it in every day. There’s just not enough time in the day.”

It’s a problem that Thompson-Saito and Vivian Bowles, both 4th-grade teachers, have often heard as they travel the state as part of the Kentucky Education Association’s (KEA) team that is training educators in the Kentucky Academic Standards for Science.

“To say that science isn’t as important as reading and math is something that we have to stop saying,” said Thompson-Saito, who teaches at Watterson Elementary (Jefferson County). “You are the professional in that room, you get to make that decision.”

In order to help elementary teachers become more confident in using the standards, which were implemented in 2014, and show them how science can be infused into other subject areas, KEA’s training team created a set of elementary science experiments, each designed to fit into a pencil box.

The nine experiments use easy-to-find, inexpensive materials and were kept small for another practical reason, Bowles said.

“As a training cadre, we have to take these across the state wherever we need to go,” said Bowles, who teaches at Kit Carson Elementary (Madison County).

Bowles and Thompson-Saito brought their pencil boxes to KEA’s annual Let’s TALK Conference earlier this month in Covington, where more than 400 teachers gathered to exchange best practices for effective teaching and learning.

In addition to time, there are other reasons why science gets squeezed in elementary schools, Bowles and Thompson-Saito said. Many primary teachers, who teach all subjects in self-contained classrooms, may not have had a lot of science training in college, they said.

Many schools and districts emphasize reading and math because those are the subjects assessed by the K-PREP test in 3rd grade, they said. Science is usually included in the test in 4th grade.

“You should teach science at every grade level K-5 for the same reason you need to teach reading at every grade level K to 5 and math at every grade level K through 5,” Thompson-Saito said. “Because those skills and knowledge build on each other from year to year.”

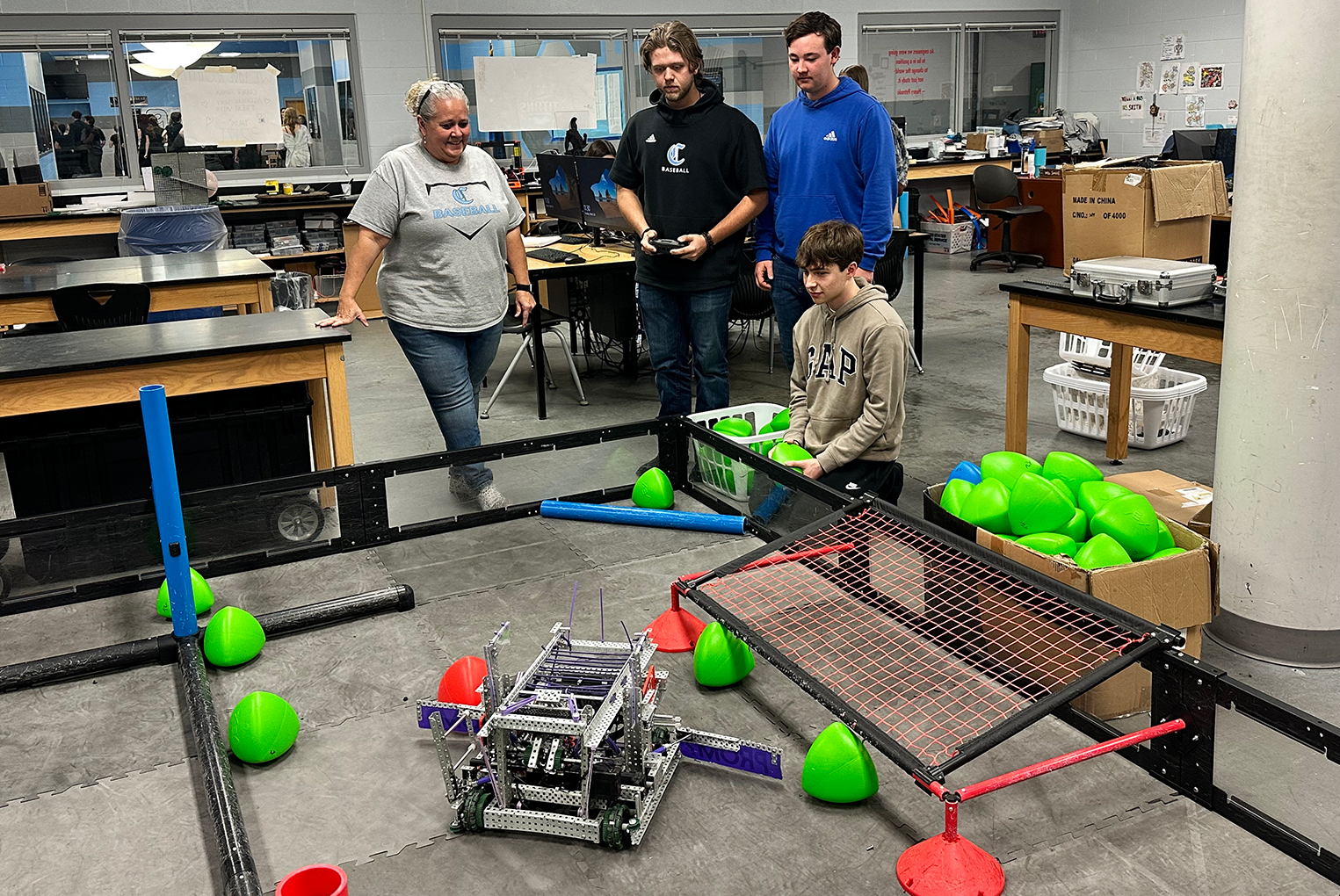

Diane Poindexter, science teacher at Cumberland County High School; Jonathan Brison, 4th-grade science teacher at Hopkins Elementary School (Somerset Independent); and Angela Richards, kindergarten teacher at Hanson Elementary (Hopkins County) build learning targets for elementary science experiments at the Let’s TALK conference.

Photo by Brenna R. Kelly, June 13, 2016

Kentucky’s science standards are designed like a brick wall, she explained. Each performance expectation is dependent on a previous one, she said. Some concepts skip a grade only to reappear in later grades.

Thompson-Saito illustrated the point with the earth systems standards from kindergarten to 5th grade written on cards and stacked on a wall. Then she pulled several of the standards off leaving gaping holes.

“If you don’t have the building blocks, the wall falls down,” Thompson-Saito said.

And that can have effects long after elementary school, she said. Students who are missing the foundational science skills taught in elementary school are likely to find science difficult and are less likely or pursue higher level science classes in high school and college.

“Those great jobs in science, technology and engineering are the ones that will go to people in India, China or Korea where there are people who have those skills and knowledge,” Thompson-Saito said.

For elementary teachers strapped for time, Bowles and Thompson-Saito recommended connecting science to reading and math. The Next Generation Science Standards website and app, both include a box for each standard that shows how it relates to the English/language arts and mathematics standards.

“In the primary grades, you can build your reading and writing curriculum using your science standards, it can be done,” Bowles said.

Thompson-Saito and Bowles also explained how to use the website and app to build learning targets for each lesson. Teachers should pick out the science and engineering practices (how scientists investigate and build models), the disciplinary core idea (what scientists know) and the cross-cutting concepts (tools which apply across science disciplines) for each of the performance expectations.

“This is what we are learning when working with teachers, that these are the things they are having trouble identifying,” Bowles said. “When teachers can identify those and start using those, lesson planning will be a lot easier.”

At the conference, teachers rotated through two of the nine pencil box stations, which included using different tools to see how birds’ beak structures help them survive, using half a toilet paper roll as a ramp for a marble to hit a target, and using an eye dropper and a small cup of water to estimate the useable water in the world.

“Teachers could set up the stations in their classroom where kids could even do science investigations on their own,” Bowles said. “You could have them do this as an extension of a lesson or during their center rotations with language arts centers, or maybe as a math center.”

Teachers used a journal to record which science and engineering practice they used, the disciplinary core idea and the cross-cutting concept of each of the stations.

Jonathan Brinson, a 4th-grade science teacher at Hopkins Elementary (Somerset Independent), said he plans to use the station about how to change the potential energy of an object with his students this year. The exercise uses a skate board and a ramp to show how the height of the ramp determines the speed of the skateboard.

The station also included a QR code that when scanned, pulled up a video about roller coasters and explained potential energy.

“I liked how they used the QR codes, that was pretty neat,” Brinson said.

Hoskins, the Bullitt County teacher, said she plans to use the pencil box experiments in her kindergarten class this school year.

“I feel like I could do more of those kinds of things in the classroom,” she said. “Just having the students in the different stations doing it on their own.”

The session also taught her how to fit more science content into her tightly scheduled day.

“It was helpful to see how you can connect the science standards to other content areas,” Hoskins said. “Because we don’t have as much time as we really need with science being at the end of the day. And they love science.”

MORE INFO …

Vivian Bowles Vivian.Bowles@madison.ky.us

Sharon Thompson-Saito sharon.thompson@jefferson.kyschools.us

Michelle New mnew@kea.org

Leave A Comment