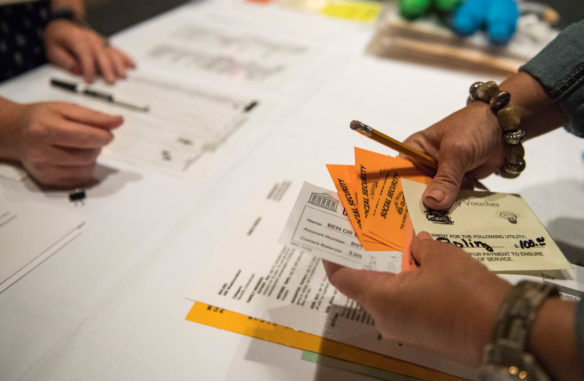

Sarah Vivian, the principal at The Academy (Franklin County), finds a card showing that she and her “family” had been evicted and received a utility shut-off notice during a poverty simulation held at the Persistence to Graduation Summit. The simulation was designed to help educators understand the problems some of their students face on a daily basis.

Photo by Bobby Ellis, June 14, 2017

By Mike Marsee

michael.marsee@education.ky.gov

Jon Wells didn’t know what to expect when he came to a poverty simulation for the first time, but he certainly didn’t expect to wind up in the pokey.

Wells was confined to jail – or at least to a corner of the room labeled as such – for a portion of the simulation held as part of the Persistence to Graduation Summit last month in Lexington.

Wells, the new principal at Hopkins County Central High School, played the role of a 17-year-old dropout. While other participants were assigned roles that kept them busy for most of the four simulated “weeks,” his character had time on his hands and sticky fingers – until he was caught by the long arm of the law.

“Man, the struggle is real,” Wells said, staying in character. “My family had $10. People leave their houses open, they’ve got more than they need and I’m just trying to get by.”

Donna Deal, manager of the Alternatives for Learning Branch in the Kentucky Department of Education’s Division of Student Success, said the simulation was added to this year’s Persistence to Graduation Summit to help educators understand what some of their students face on a regular basis.

“Poverty is a reality for many people in Kentucky, but unless you’ve actually experienced poverty, it can be difficult to truly understand,” Deal said. “We hope that the simulation allowed participants to gain a personal understanding of poverty, as well as explore and discuss strategies that districts and schools can utilize to positively impact students and families who may be living in poverty.”

Jon Wells, the new principal at Hopkins County Central High School, reacts after being arrested and taken to jail during the poverty simulation. Wells said he thinks most teachers don’t truly understand the circumstances faced by their students who live in poverty.

Photo by Bobby Ellis, June 14, 2017

According to the 2017 Kids Count Data Book report produced by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, 26 percent of Kentucky’s children – about 256,000 kids – lived in poverty in 2015.

The poverty rate was 100 percent in the simulation led by Katherine Cooter, the executive director of the Kentucky Council for Economic Education at Bellarmine University. Cooter offers the training in an attempt to help participants, including the 110 educators who attended the Persistence to Graduation Summit, gain a personal understanding of poverty.

“I think our goal is empathy,” Cooter said. “Often teachers and others have sympathy or antipathy, but here you’re going to walk in someone’s shoes for a while, and you’re going to experience some of the daily stressors of living in poverty circumstances.”

Cooter was a classroom teacher for 17 years, and she said her goal is to help educators realize where some of their students are coming from.

“I think that they learn about what kids carry in their emotional backpacks, that kids come from families where mom is stressed, where dad may have trouble getting a job, where they didn’t get to pay their rent on time,” she said. “They’re making some choices that are difficult.

“For a child, the line between what happens at home and what happens at school is not that clear. What is happening at home in terms of frustration, tension, anxiety and stress affects every part of their lives.”

Wells, who is moving from an elementary school to a high school, said teachers realize that those factors affect students at all levels, though it isn’t always evident.

“The younger kids can’t hide the effects of being in an environment like that, whereas in a high school the kids are able to pass themselves off as normal,” he said.

Participants in the simulation were assigned to families as they entered the room. Some played the role of adults and others played children for four 15-minute “weeks,” but all were in poverty scenarios.

“They’re going to make some choices to buy medication or groceries, to pay the electric bill or feed their children,” Cooter said.

They moved among a dozen or so stations at which they could do things such as attend work and school, pay utility bills, buy food or medicine, apply for assistance or get a cash advance. There was play money, but transportation passes also became a kind of currency, which underscored the importance of being able to get from place to place.

Participants in the poverty simulation trade transportation passes at one of the stations. Transportation passes became a kind of currency that illustrated the need for students and their families to be able to get to school, work and other places, underscoring another problem those living in poverty often face.

Photo by Bobby Ellis, June 14, 2017

Carla Kent, a college access resource teacher at Iroquois High School (Jefferson County), played a 14-year-old girl in a single-parent home.

“In our ‘family,’ we have a single mom and our dad ran off. We’re having to navigate through what to do as a family, and I’m looking through the lens of a 14-year-old,” Kent said. “There’s not much I can do as far as work, but I feel the stress of not having the resources I need. I had to have $5 for a field trip and my mother couldn’t afford it, so I felt like a 14-year-old would feel not having the money that I needed.”

Criminals and truants found themselves in the custody of police officer/jailer Jerry Reynolds, one of several participants who were drafted to man the stations.

Reynolds teaches at McCreary Academy, the alternative program in the McCreary County school district, and he said he is familiar with many of the situations in which the simulation participants found themselves.

“I know about a lot of the situations that we’re looking at today,” he said.

He said, however, that there was still a great deal he could learn from this simulation.

“I want to be able to better address my students. They bring so many different things into the equation,” Reynolds said. “You can’t just use a cookie cutter. We have to address their needs individually.

“What we hope to do is get kids into school, keep them there regularly and get them a diploma.”

Kent said she sees many of the same scenarios that simulation participants faced in the halls of Iroquois High.

“We have a high-poverty, low-performing school, and it happens every day,” she said. “I think every teacher needs to go through this process to know how our students feel and how to best support them. It’s hard for a student to think about reading, math and writing when they have these real-life situations going on at home. They can’t stop thinking about it when they come to school.”

Cooter noted that Monday is often a difficult day at school for students in poverty because of what they bring with them from home.

“They’re making a dramatic culture change from home to school on Mondays, different rules, different sets of behaviors that are acceptable and not acceptable, so those are hard days for them,” she said.

Wells said he thinks most teachers don’t truly understand those circumstances, even if they believe they do.

“No, teachers probably don’t know,” he said. “Obviously there are some that have come through that or can relate through family experiences, but for a lot of teachers, at least in my experience, they really can’t relate to that.”

MORE INFO …

Kathleen Cooter kcooter@bellarmine.edu

Carla Kent carla.kent@jefferson.kyschools.us

Jerry Reynolds jerry.reynolds@mccreary.kyschools.us

Jon Wells jon.wells@hopkins.kyschools.us

[…] Are you ready to address your students’ needs? Read more in Getting a glimpse of what poverty feels like at http://www.kentuckyteacher.org/features/2017/07/getting-a-glimpse-of-what-poverty-feels-like/ […]