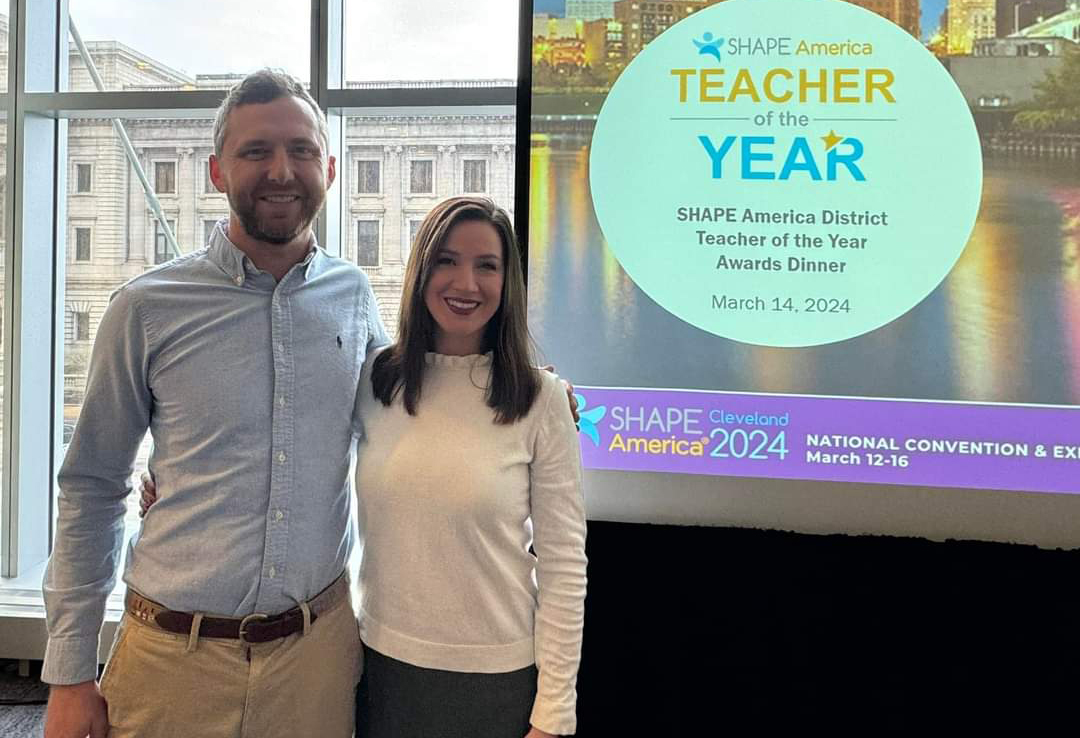

Commissioner Terry Holliday, Gov. Steve Beshear and First Lady Jane Beshear celebrate all 173 Kentucky school districts raising the dropout age from 16 to 18 during a press conference at the Capitol.

Photo by Amy Wallot, Jan. 29, 2015

By Mike Marsee

michael.marsee@education.ky.gov

Kentucky schools can celebrate a major victory in their battle to keep students from leaving school early, but only for a little while. Then it will be time to get right back to work.

A milestone has been reached with the adoption by every local school board of a policy that raises the compulsory attendance age from 16 to 18, which has been a priority for the Kentucky Department of Education (KDE) and a focus of Gov. Steve Beshear and First Lady Jane Beshear.

The last of the 173 boards of education to adopt that policy did so last month, and Gov. Beshear, First Lady Jane Beshear and Kentucky Department of Education Commissioner Terry Holliday marked that event with a celebratory press conference last week.

“A higher mandatory attendance age was one of my legislative priorities and has been ever since I took office 7 1/2 years ago,” Beshear said. “We want every student to come out of school prepared to succeed at whatever’s next in his or her life.”

The Beshears and Holliday thanked local boards of education at the press conference for their efforts to raise the compulsory school attendance age in just over 18 months, but the governor and first lady also made it clear there is much more to be done.

“Raising our expectations shows that we care about our students’ futures, which I believe gives them a reason to succeed,” said Jane Beshear, whose husband called her the “chief lobbyist” for this initiative. “We’re looking to school districts, teachers and administrators to get creative to find ways to engage our at-risk students, to get them back into the fold.”

Work will continue toward that end at the local level, where many districts are still using the $10,000 planning grants they received from KDE to plan for implementation of the higher dropout age, and all of them remain engaged in keeping students in school.

“We’ve got to get in their heads and figure out what we need to do to make them understand education is very vital for them if they’re going to have productive lives,” Pulaski County schools superintendent Steve Butcher said. “That’s got to start in kindergarten.”

Making the law work locally

There is a growing list of examples of how to do that, and some of that work has been supported by the planning grants. The first 96 districts to vote to raise their dropout age – the number needed to make the policy change effective statewide – received their grants in fall 2013, with a second round of grant checks going out at the start of the current school year and the final round going out just last week.

“We’re currently in an effort to communicate with those early implementers of SB 97, and we will continue to share lessons learned from some of those early pioneers, and the ones coming on now will benefit greatly from those folks,” KDE Chief of Staff Tommy Floyd said.

The new compulsory attendance policy was supported by the Kentucky School Boards Association (KSBA), which helps local boards adopt and modify policies relating to state statutes and regulations, KSBA director of member support Brad Hughes said.

“We were behind the initiative to get the boards to adopt the polices, and we’re behind the law,” Hughes said.

It replaces a law that has been on the books since 1934, and Hughes said it eliminates local policies that allowed students to leave school prior to turning 18, such as in cases of parental consent or marriage. It takes effect in all but eight districts in the 2015-16 school year; it will be effective in one district the following year and in seven more in 2017-18.

Many local school boards rushed to be among the first to pass such a policy – some even called special midnight meetings to be among the first schools on board – and the 96-district threshold was reached within about two weeks.

A few of them may have been motivated by the planning grants, but Butcher said that wasn’t the driving force in Pulaski County, which was among those districts that voted to raise their dropout age on the first day they could do so.

“The grant is not what prompted us to do that,” Butcher said. “Ten thousand dollars is not a lot of money. We just felt as educators that it was important for us to step up to the plate and let people know that we didn’t want anybody to drop out.”

Many uses for planning grants

Butcher said the grant was his district’s grant money was used for interventions, which was one of the top uses for those funds based on a survey that included the first 96 districts.

Other main areas in which funds were used were digital and virtual curricula, alternative education programs and support and staffing. Some districts also used the grants for equipment and technology, job shadowing, mental health counseling, college visits and even a school newspaper program for at-risk middle school students.

“One of the calls that we received that I thought was a creative way of using the grant money was to purchase cribs, because that district has a program for parenting students to help support them in staying in school, but they were a few beds short,” said Christina Weeter, the director of KDE’s Division of Student Success.

Floyd said good ideas have emerged across the state.

“We have a number of districts who are great examples of how they have fine-tuned their offerings to really be based around the needs of individual students,” he said.

The importance of early identification

Tom Edgett, the Alternatives for Learning branch manager in the Division of Student Success, said it is also important to identify at-risk students as early as possible.

“Every conversation we have with a school about their dropouts, we say, ‘A kid did not drop out at 16. They left school at 16; they dropped out years ago, and they were just biding their time,” Edgett said. “I was a middle school teacher for 15 years, and I could’ve told you from among my seventh-graders who was going to drop out. They’re only 11 and 12, but I knew. And we’re trying to catch those kids and meet their needs.”

KDE is supporting that through its Persistence to Graduation Tool (PtGT), an indicator system within Infinite Campus for identifying students who might be off track for promotion or on-time graduation that Edgett said is being utilized in 35 to 40 percent of Kentucky’s districts.

“It’s an early-warning system. It takes all the demographic information in Infinite Campus, all of the risk factors, and it gives the kids a risk value, and it ranks them,” he said.

Bringing dropouts back to school

The change in the dropout age creates a group of teenagers who have already left school early but must now return. The statute created by SB 97 does not exempt students who have already dropped out; under the law, 16- and 17-year-olds must be in school when the higher dropout age takes effect in their district and must remain there until they graduate or turn 18.

“We’ve sent every school in Kentucky a recent list of their dropouts and asked them to start planning on how they’re going to recover them, because (soon) all the districts will have to recover anybody under the age of 18 that has dropped out,” Holliday said.

The KSBA’s Hughes said that organization stands ready to help districts in the event of legal challenges in that or other areas.

“There will be a few. I’m sure there will be legal questions that come up,” he said.

Weeter said KDE wants to ensure that those students aren’t simply pushed off to the side after they return to school.

“We want to make sure that schools understand that this is an opportunity for them to really reach these students, maybe in a different way than they were working with them before. There’s going to have to be a little bit of a mind-shift there,” she said

Butcher said Pulaski County will try to reach those students by identifying the issues that caused them to leave school and by giving them an incentive to want to stay. For example, if a student felt he needed to drop out to make money for his family, the school might help them find ways they can continue to do so while continuing their education, perhaps through career and technical centers.

“We’ve got all different kinds of plans for different kids, and you’ve just got to think outside the realm,” he said. “We’re saying, ‘Look, we’ve got to make this work for you.’ It’s not necessarily going to be seat time for them where they’re going to sit in class for six hours a day. We’re looking at other performance-based ways for them to get their education.

“We’ve got to do something different, because they are different.”

Jane Beshear said there is much work still to be done in all areas of dropout prevention, but she said raising the compulsory attendance age sends a strong message.

“We all know that this measure is not the silver bullet. It will not magically fix those children’s problems that drop out or wanted to drop out,” she said. “But by adopting this policy, we are letting our students, our parents and our teachers know that we expect them to succeed, and that we believe that they are capable of success.”

MORE INFO…

Steve Butcher steve.butcher@pulaski.kyschools.us

Tom Edgett tom.edgett@education.ky.gov

Christina Weeter christina.weeter@education.ky.gov

Leave A Comment