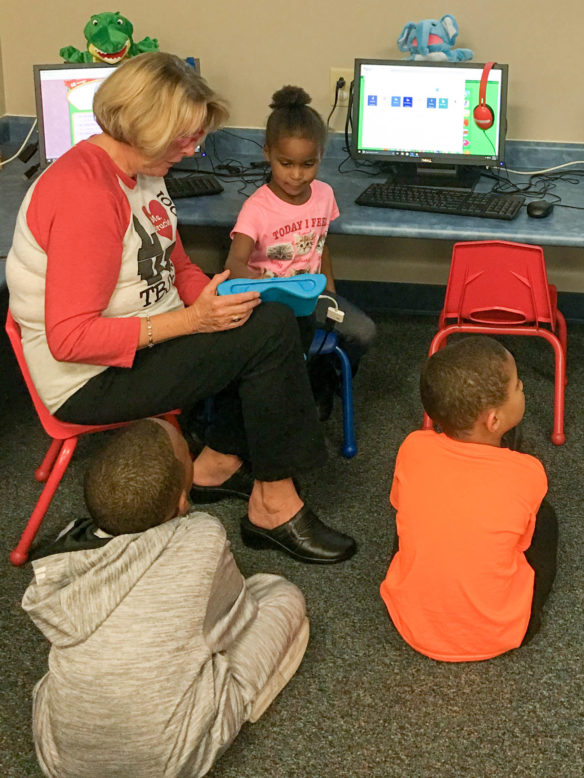

Henderson County district substitute and retired educator Brucie Farris teaches a class at the Thelma B. Johnson Early Learning Center to code using Daisy Dino on the iPad in the library. Even though school librarian Rhea Isenberg thought her practices were engaging and progressive, she discovered she could be doing more after she started trying to obtain her National Board certification.

Submitted photo by Rhea Isenberg

On a recent day in the media center at the Thelma B. Johnson Early Learning Center (Henderson County), a group of 3-, 4- and 5-year-olds checked out books with their teacher. A small group of 3-year-olds extended their learning from the classroom using a coding robot that followed codes given by the students. Meanwhile, I worked on a Makerspace activity that guided students to build their own snowmen from healthy and unhealthy foods, which built on a read-aloud I had conducted.

This is our media center. It’s a place to extend and expand on student learning, a place alive with student voices and student growth.

Rhea Isenberg

Not so long ago, my students came to the library for a lesson, just like many elementary and preschool students. The students usually participated in a read-aloud, sang songs about their learning, fine-tuned their computer skills using the computer lab and interactive websites, and checked out books. All in all, I judged my interaction with the students to be very engaging and progressive. After all, I do teach in a preschool center and weekly library lessons are not commonplace to most preschool students and teachers.

However, after beginning my National Board candidacy and reading the organization’s library media standards for preschool through 12th grade, I suddenly felt inept.

Preschool centers with certified early childhood teachers, like the one where I work, are rare. A certified library media specialist in those libraries is even more unusual. In fact, there are only 35 such preschool centers in the state of Kentucky. Despite my certification, the idea of engaging preschoolers in student-led research and integrating technology for investigative purposes was completely foreign to me.

Yet what I have discovered over the past few months during my journey to meet the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards has forever changed my perspective on library media centers and their role in our public schools.

What I found most interesting when reading through the standards is that the lessons I traditionally taught in the library media center were not exemplary. For example, Standard 3, Knowledge of Library and Information Studies, says the best library media specialists make their media center a place where teachers can apply and seek to understand the integration of technology. Standard 6 maintains that the best library media specialists use the technology in creative ways to support student learning in the 21st century.

These standards in no way reflected my former library routine, which was missing integration and innovative use of technology. I debated giving up my pursuit of National Board certification, telling myself there was no way I could begin to do this, especially with preschoolers. Instead, I decided to dig deep and change my mindset.

As I read through the standards in the spring of 2015, each one motivated me to shift my practice. Standard 4, Leadership, taught me that the best library media specialists are leaders in their schools and in the profession. In order to begin my journey of implementing this standard, I started in a familiar place – the Kentucky Library Media Specialist listserv.

I was looking for something I could implement easily, with long-lasting effects, and I found just what I was looking for – coding with robots. What could be more innovative and hands-on than coding with fun and interactive robots?

However, once I got those awesome pieces of technology, I found it overwhelming to understand how they worked, let alone understand how to show my fellow teachers, librarians and students. So I contacted a professor at Western Kentucky University and she helped train our district library media staff and preschool staff on coding before the start of the school year. I felt like I was starting to make the media center a place where innovation happens, and I also felt my confidence beginning to grow.

This school year, I have expanded the coding lessons to include the Fisher-Price Think & Learn Code-A-Pillar and its free app, a Bee-Bot, and a Code & Go Robot Mouse. The teachers even check out our coding technology for use in the classroom.

The National Board standards encourage library media specialists to promote the library media program through the development of advocates. I began reaching out to stakeholders in the community and engaging them in the life of the media center. I also helped prepare our preschool students for their visits. For example, when these guests and community partners were collaborating with classrooms, I led students to form questions for them during a large group activity prior to their arrival. This helped the preschool students engage with our guests and understand the significance of their visit.

I also collaborated on coding in the spring of 2017 with Murray State’s Kentucky Academy of Technical Education (KATE) program – which provides support, training and resources to empower educators to utilize technology in their classrooms – and a district middle school robotics teacher. The middle school students coded the robot provided by the KATE program with gross motor movements, and my preschool students mimicked the movements to help them prepare for kindergarten. My students then began to code with an app after “moving” with the robot for a couple of weeks. It was a win-win for both the middle school and preschool students

The National Board standards also state that the most skilled librarians understand and apply the principles and practices of effective teaching in support of student learning. As a result, I began using apps on our school iPads for coding, presentations and skills practice so students could use them with teacher support in the classroom to expand upon and enhance their learning. I also looked for apps that would allow the students to practice their integration of technology so they could continue to build their 21st century skill sets. One such piece that our students and teachers enjoy are our Tiggly apps for reading and language.

My son summed up my role best one afternoon when he commented, “Mom, there’s way more to your job than shelving books.” As long as educators’ views of teacher librarians continue to evolve and change, libraries and media centers will have an essential place in our schools.

I’ve learned so much in my candidacy, but more than anything, I’ve come to the realization that as a library media specialist I must challenge myself to innovate and encourage my students to be active learners. Whether it is by making and creating or by researching and investigating, students and teachers can be impacted significantly by the teacher librarian and the ever-evolving hub of the school library media center. I challenge myself each and every day to see my teaching through the lens of the National Board Standards and I hold myself accountable to meet them.

I decided to try to become certified because I wanted to push myself as an educator and be better for my students. There is no more effective route I could have taken to positively impact student learning.

Rhea Isenberg is the school librarian at the Thelma B. Johnson Early Learning Center (Henderson County).

Leave A Comment