Education recovery leader Susan Brock, left, counselor Mary Feltner, center, and Educational Recovery Specialist BJ Martin meet with school leaders at Leslie County High School Jan. 5, 2011. Behind them, data walls help track student progress on assessment. Photo by Amy Wallot

By Matthew Tungate

In the spring of 2010, Kentucky identified the first group of 10 persistently low-achieving schools to receive federal money and state help to improve after years of struggling to improve student test scores. For most of the state, it was the beginning of a new school-turnaround model. For 24-year veteran teacher Donna Asher, it was her livelihood.

“It was embarrassing,” the Leslie County High School mathematics teacher said. “It was implied that all our teachers were not doing their jobs, and this wasn’t true. We had about five who were not doing their jobs. I knew our students and staff were much better than what the test scores implied. We were capable of so much more. We just needed better leadership with a better focus on what’s most important: the best possible education for our students.”

But Asher has gone from embarrassed to appreciative after attending training over the summer for what was ahead of her and seeing those teachers leave the school.

“I was on board and wanted big changes in the school,” she said.

Big change is exactly what is expected from the persistently low-achieving schools and the new school-turnaround model, passed into law one year ago. District 180, as the model is known, provides money from federal School Improvement Grants (SIGs) and state-paid specialists for three years to help improve school performance. District 180 uses experienced teachers, called education recovery specialists (ERSs), to go into schools to help teachers improve mathematics and reading instruction.

BJ Martin, ERS for reading and in her 11th year in education, and Linda Hall, ERS for mathematics and in her 23rd year in education, have been working with teachers at Leslie County High this school year.

Martin said she has found that teachers are working hard.

“Teachers are not making excuses for where their scores were,” she said. “All stakeholders (administration, teachers, ERS Team, parents, students and community), just want to improve and be the best school possible. It is important to everyone here to be successful.”

Some improvement tips typical among schools

Sally Sugg, former director of District 180 for the Kentucky Department of Education, oversaw the model’s implementation and said ERSs throughout the state will do some common things to help schools.

“All teachers are working hard,” she said. “But what we’ve found is a lot of teachers work extremely hard, they collect a lot of data, but then they don’t know what to do with the data.”

So ERSs help teachers analyze data and make changes in their practice, she said.

Schools are required to turn in quarterly reports that ask for specific data, including 9th-grade failure rates in mathematics, language arts, science and social studies, “because we know that leads to dropouts,” Sugg said.

Martin said Leslie County High is “continuously collecting and analyzing data (walkthroughs, formative and summative assessments, attendance, professional learning community [PLC] meeting minutes) to determine if what we are doing is effective. We use administrative and collegial walkthroughs weekly to help us determine what our strengths are in the classroom, as well as areas that we can better support our staff and students.”

Teachers also are required to give benchmark interim assessments, Sugg said.

Those assessments help teachers determine gaps in the curriculum, as well as appropriate interventions for students who need additional help meeting standards, Martin said.

ERSs work with their corresponding education recovery leader (ERL), who works in the same way with the principal at low-achieving schools, to hold teachers and principals accountable for doing what they say they will do in school-improvement plans.

“That happens in good schools, that happens in effective schools, but in some of these schools that’s not happening systematically,” she said. “So we’re putting that system in place so that everybody’s accountable for what they said they were going to do. And that is the difference between our high-performing schools and districts and some of these schools that are not high-performing. The system is not in place, so that’s what we’re trying to do: set up the system so that when we leave, that system can continue.”

ERSs also try to ensure that professional learning communities (PLCs) are focused and productive during meetings, Sugg said.

Hall said all departments stay after school one day a week for 60-90 minutes.

“They receive no extra pay or professional development hours for their hard work and dedication,” she said. “This commitment comes from a sincere desire for their students to receive the best.”

The weekly PLC meetings allow teachers to keep “a laser focus on what is best for students,” Martin said.

“Each meeting has its own purpose, but student achievement is at the forefront,” she said. “One of the responsibilities of each department has been to create a new curriculum based on the Common Core Academic Standards. Teachers meet not only to align the curriculum, but also to develop instructional plans that will meet the needs of each individual student. Much of their instruction includes best practices and the work of (Rick) Stiggins, (Robert) Marzano, Fred Jones and others.

Ultimately, ERSs and ERLs are trying to help put in processes, strategies and structures so “at the end of that three-year period when they no long have the SIG money or the state or federal help, that those teachers and those principals and those buildings and those districts will be able to continue on with that same type of systematic continuous improvement,” Sugg said.

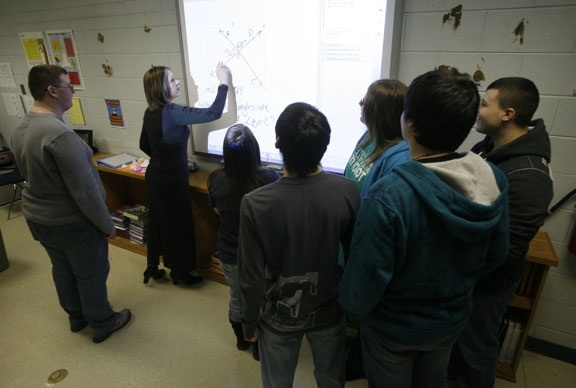

Resource teacher Crystal Farler works a geometry out on a SMART board with her students’ help at Leslie County High School Jan. 5, 2011. Photo by Amy Wallot

Leslie County High has used specific strategies to improve

Asher said she has been impressed with some specifics that Hall has brought to the school.

“We have implemented Response to Intervention (RTI), mentoring extra math classes. Linda has helped with PLC meetings, showing us good strategies for formative assessments. She has helped us roll out the new core standards using new unit plans and daily lesson plan formats utilizing the new teaching strategies,” Asher said.

Special education teacher Crystal Farler, who has spent more than half of her seven-year career at Leslie County High, said Hall has been a great resource to her, and she has seen the effects in her classroom.

“I am the only special education teacher to teach math or collaborate in a math classroom,” Farler said. “If I need anything, she will make sure that I have it.”

Leslie County High began turning around even before Hall and Martin arrived. The school improved the number of students scoring proficient or distinguished in reading and mathematics by 24.25 percent, the most of any of the 10 schools identified as persistently low-achieving. It also met its annual yearly progress goals required by the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

Hall and Martin both credited two people for that change: Principal Kevin Gay and Highly Skilled Educator Susan Brock.

Gay “offers no excuses for scores,” Hall said. He believes that students in the school are capable of higher levels of learning and expects that Leslie County High will become one of Kentucky’s best, she said.

Highly skilled educators (HSEs) were part of the previous intervention system where experienced educators would spend two years helping turn around a struggling school. Brock worked with the administration to change the school’s culture and expectation of success, Hall said.

“Special attention was given to attendance of students and teachers,” she said. “Students were assigned mentors to encourage and work with them on specific skills, based on individual student needs. There were also slight changes in scheduling that improved the needs of students. Concentration on instructional practices and formative assessment began last year and are carrying seamlessly on into this school year.”

HSEs are just one of several strategies that Kentucky has used to turn around struggling schools, said Sugg, herself a former HSE.

Lessons learned

One thing educators have learned is “Nothing will happen unless leadership is addressed both at the district and at the school level,” she said.

Numerous districts have received support and resources, but not improved significantly, Sugg said. That can be attributed to leaders who were either reluctant or otherwise not on the same page with those trying to help them, she said. Under District 180, the ERL is there to mentor the principal.

Prior turnaround models also had state education experts as advisers only, Sugg said. HB 176 requires the state to assess school and district leadership to determine if they are capable of improving the school.

That’s leading to more cooperation, Sugg said, because “principals, school-based councils and districts know that the leadership assessment is going to determine whether they can continue in that capacity.”

The state also has learned that “teachers all want to do a good job,” she said, but they may not know the best way to do so.

“Some of the teachers, especially in some of our rural districts where a lot of the leaders are wearing five different hats, they just don’t get a lot of the information they need,” she said.

Review teams have found pockets of excellence at all low-performing schools, Sugg said.

“The principal’s job and the district’s job to support that is to make sure that those best practices get replicated with consistency and fidelity across the school so that all kids are getting what they need, not just those in those teachers’ classes,” she said.

Finally, Sugg said, the Kentucky Department of Education realizes it can’t do everything. So the District 180 model incorporates universities, educational co-operatives, communities and parents.

“We’ve learned that through all of the various models we’ve had, starting from the distinguished educator – which was sort of the lone person going into a school – all the way up through VPAT and ASSIST, which brought resources together to the table, and we’ve seen how productive that is to have all those resources sitting together and working with the superintendent and all the people that are there to assist the schools.”

Martin and Hall also like that District 180 is building capacity within schools.

“The education specialists are not fixing problems, but inspiring and leading others to fix their own issues to become a highly successful organization,” Hall said.

MORE INFO …

Linda Hall, linda.hall@education.ky.gov, (606) 672-5580

BJ Martin, bj.martin@education.ky.gov, (859) 582-1760

Leave A Comment