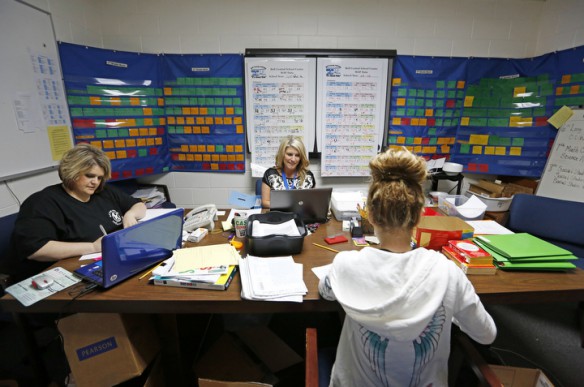

Assistant Principal Jennifer Wilder, counselor Kara LeFevers and AmeriCorps worker Amelie Miracle work in a conference room surrounded by color-coded student progress information at Bell Central School Center (Bell County). Photo by Amy Wallot, May 15, 2013

By Matthew Tungate

matthew.tungate@education.ky.gov

In just three years, the Bell County school district more than tripled the rate of students considered college and career ready.

The reasons for their success vary, with principals and staff at the district’s high school and combined elementary/middle school citing strong alignment to the new Unbridled Learning accountability system and corresponding academic standards, dedication to meet individual student’s needs, and partnerships that have made college admission an expectation.

But there also is a less tangible and no less important reason that schools in the county nestled deep in southeastern Kentucky are improving, they said.

“We love them and treat them like our own,” said Susan Brock, a 4th-grade science teacher at Bell Central School Center. “If they go out and they fail, then we fail.”

Nanette Hensley, assistant principal and curriculum coach at Bell County High School, agreed, saying educators at the school love and care about the students as they want others to care about their own children.

“And that climate is so powerful in a school system,” she said. “Those are things that you can’t really tally or test.”

But the results are undeniable. Jenny Todd, a research analyst with the Kentucky Department of Education (KDE), is studying districts like Bell County that exceeded their college- and career-readiness targets the last two years.

In February 2011, KDE secured the Commonwealth Commitment from all districts to move 50 percent of their high school graduates who are not college- and/or career-ready to college- and/or career-ready between 2010 and 2015.

Todd wanted to know how some districts exceeded those annual targets, so they went to Bell County last fall and interviewed district and school administrators, and teachers from three schools, including Bell Central School Center and Bell County High.

She came away impressed with how Bell Central School Center teachers use a color-coded data wall that shows how close every student in every grade is to working on grade level in mathematics and reading. Students are coded as red if they are far from grade level, yellow if they are approaching grade level and green if they are at or beyond grade level.

“You could see trends where a lot of kids might struggle at the lower levels and by the higher grades more of the kids had moved to green,” Todd said.

Principal Greg Wilson said students take Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) assessments in the fall and change colors as needed in the winter and spring.

“We can automatically see how many students in the 6th grade, for instance, are above grade level in math, how many are borderline and how many need intensive remediation,” he said.

Tina Lambdin, a middle school math teacher, said teachers use Response to Intervention (RtI) time and corrective classes if students are in red. Students also are placed in enrichment classes depending on their color, she said.

“If a group is accelerated or above average, we will teach them one set of concepts,” Lambdin said. “A class that’s average, we will teach them the concepts they need, and a class that’s below average we will teach to their individual needs.”

Wilson said most kindergartners come to school below grade level, so they have the highest percentage of red. The older students get, the higher the percentage of green, he said.

“The goal is to get them on grade level as quick as possible,” he said.

Similarly, students in the high school are grouped in math classes based on MAP, EXPLORE and PLAN tests and grades, according to Principal Richard Gambrel. That way the teacher can intensify his focus on a group of students with similar needs, he said.

“So we can really meet the needs of the students as they come into the class,” he said. “We know where they are, what they need and how to get them to where they need to be before they graduate.”

For seniors who have not reached the college readiness math score on the ACT, math teacher Josh Garnett teaches four transitional classes. He tries to help students reach college and career readiness on KYOTE.

He motivates them by saying they can get out of remedial math in college if they can reach a 22 on KYOTE.

Hensley said it is a good strategy for seniors already taking one math class.

“A lot of kids want to get out of taking a second math class,” she said. “They’re motivated to pass that KYOTE.”

Gambrel said the school changed its focus with the Unbridled Learning: College and Career Ready for All accountability system. The school is more ACT-driven and encourages students to become college and career ready through other methods than the ACT, such as KYOTE, when necessary.

“Our teaching staff has taken the initiative that they want our kids to be successful, they’re stressing the importance of ACT, they have bought into the focus of ACT because they know how important it is now, and we know how important it is for our kids to be college and career ready,” Gambrel said.

The school also partners with AdvanceKentucky, which has accelerated the school’s curriculum, Hensley said.

“So they’re getting a higher-level curriculum than we’ve ever been able to offer before,” she said.

The school also revamped its math program in recent years, with teachers using a new curriculum map.

“That is offering some opportunities for students to excel in ways they’ve never gotten the chance to before,” she said.

Elementary and middle schoolers at Bell Central School Center also are getting college and career ready through GEAR UP (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs). Now two years into the program, every student from 2nd through 8th grade has taken a trip to a college campus, Wilson said.

“That’s caused us to think a little differently, having that grant in our district,” he said.

The school also focuses almost exclusively on reading and math in grades K-3, Wilson said. Students spend about one and a half hours on math and three hours on reading each morning, and then language arts, science and social studies in the afternoon. Students who need intervention in reading or math are pulled out in the afternoon for extra support, he said.

“We figure if we can get them to read and do math by the end of the 3rd grade, we can teach them science and social studies from 4th grade on,” Wilson said. “We learn to read until 4th grade and after 4th grade we read to learn.”

K-PREP tests only reading and math in 3rd grade.

“I know science and social studies are important and arts and humanities are important also, but if they can’t read the science and social studies material, they’re going to struggle, so we want to build a real, real strong foundation in that,” he said.

And it doesn’t seem to be hurting the students in social studies or science, Wilson said, as students scored 100 in both subjects on last year’s K-PREP.

Brock agreed, saying students have struggled to read her science tests in previous years.

“Now that’s never the case. Even our special needs teachers don’t have to be pulled to sit with them and try to give a test to special needs kids because they can all read the test,” she said.

MORE INFO …

Richard Gambrel, richard.gambrel@bell.kyschools.us, (606) 337-7061

Greg Wilson, greg.wilson@bell.kyschools.us, (606) 337-3104

Kate Akers, kate.akers@education.ky.gov, (502) 564-4201

Jenny Todd, jennifer.todd@education.ky.gov, (502) 564-4201

Leave A Comment