John Scott Brewer, who teaches at The Phoenix School of Discovery (Jefferson County), uses Magic the Gathering cards as a point system for students in his 11th- and 12th-grade alternative placement English classes at the optional alternative school. Brewer employs a gamification strategy using a website that features game-design elements and principles to help them take more ownership of their work as they improve their ability in reading, writing and language mechanics.

Photo by Bobby Ellis, July 23, 2018

By Mike Marsee

mike.marsee@education.ky.gov

John Scott Brewer isn’t playing games when it comes to helping his students master reading and writing. His students are, though.

Students in Brewer’s 11th- and 12th-grade alternative placement English classes at The Phoenix School of Discovery (Jefferson County) improve their ability in reading, writing and language mechanics as they work their way through multiple paths to success.

Brewer employs gamification by using a website that features game-design elements and principles for his students at his school, an optional alternative program. He detailed his approach in June at the Persistence to Graduation Summit held by the Kentucky Department of Education (KDE) and AdvancEd. He said one of the primary goals of his course is to increase student ownership of their academic success while aligning each student’s portfolios toward their postsecondary employment goals.

“It’s obvious that students take more ownership as their work becomes more about their focus and their goals,” Brewer said.

Christina Weeter, the director of KDE’s Division of Student Success, said Brewer’s approach is an excellent example of a way to reach at-risk students and the very kind of work the Persistence to Graduation Summit was designed to showcase.

“Teachers, schools, and districts are coming up with some very creative ways to keep students engaged in school until they graduate,” Weeter said. “Through the Persistence to Graduation Summit, we are trying to shine a spotlight on how this is being done across the state. The hope is that Summit participants will learn about a strategy, technique or policy that they could potentially implement in their own community.”

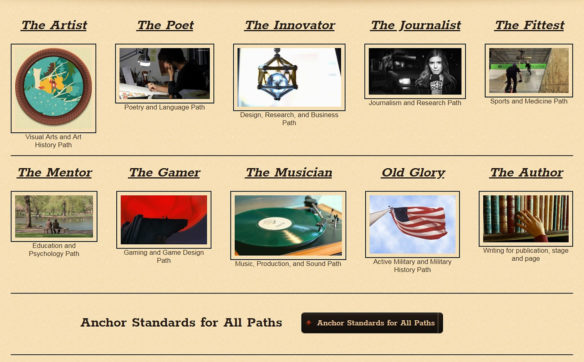

There are 10 themed paths based around the standards for the course through which students work to prepare their portfolios. The paths – artist, poet, innovator and gamer are among the choices – are outlined as “keys” on Brewer’s website, along with project options for each key and the standards to which they align.

Brewer said the entire class isn’t built around the multi-path curriculum, only the portion in which students are working on their portfolios. However, students are also given some freedom to choose how their time in class is structured during daily station work, in which students read an assigned novel and answer questions designed to reference the close reading and grammar work the class is already pursuing. Students also use the website to access that work.

A screenshot from a page on John Scott Brewer’s website, kingdomandkeys.com, shows the 10 paths from which students can choose as they work through their portfolios.

Students have the most control over their learning during their portfolio defense – the process in which they compile and present evidence that they have mastered the standards – as they work their way through options within their chosen path. They are to complete one key project every two weeks using the options within their path, and those projects help them develop skills they can use in employment.

“The results that I’ve seen are a huge increase in the student output when it comes to their portfolios, because they really are their portfolios and not just my portfolios that they’ve completed,” Brewer said. “I really love that, and participation in the completion of their final portfolio defense has gone up a ton since my first year.

“Once you have a portfolio with skills that are going to get you employed, it truly is yours.”

Students who complete a path and demonstrate employable skills get their names on a classroom wall of fame. Brewer said his students also get the knowledge that they have skills they can use when they leave school.

Brewer uses gamified behavior tracking to track students’ participation and progress using what he calls “experience points.”

“Gamified behavior tracking is a game-like structure designed to increase positive student academic and emotional engagement,” he said.

Individual students do not compete against each other, but his two classes compete against each other for small weekly rewards.

Brewer said gamification has been effective for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and generalized anxiety.

“ASD students tend to struggle with schoolwork when it does not have obvious real-world application, so reframing standards to match their personal employment goals increases buy-in,” he said. “For ODD students, the need to rebel against authority is very real, and when the standards are all presented in one method to the class, it allows for easy rebellion. Multi-path teaching allows for ODD students to assign themselves a path, which removes the authority figure from the equation when getting to work.

“For generalized anxiety students, having assignments that are designed to meet their personal narratives makes schoolwork less threatening, because it is driven by their interests. Also, because students can design their own key projects – which I then align to the standards – there is a greater sense of attainability of the projects since they come from the students themselves.”

He said a smaller version of his multi-path system could be implemented by any teacher in a relatively short time.

“If you start with two or three paths, it’s not going to be as big a time commitment as with 10 paths,” Brewer said. “You could probably fill out two or three paths and make them viable within a month or so, especially if you’re working with other teachers in your content area at your school.”

Not surprisingly, Brewer is a game player himself. He is a dungeon master for a Dungeons and Dragons group, and he said there are parallels between that role and his teaching.

“DM-ing is great practice for teaching,” he said. “You have a whole bunch of people trying to do their own thing while you work toward a goal.”

He said gamification has worked well for his students at The Phoenix School, a school of more than 400 students that considers students’ specific social, emotional and academic needs and stresses their involvement in their own learning. He also said it has been effective for students with autism spectrum disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and generalized anxiety.

“Historically we don’t have a lot of students in college,” said Brewer, “but we’re seeing more and more kids every year go into four-year institutions, and that’s really exciting.”

MORE INFO …

John Scott Brewer john.brewer@jefferson.kyschools.us

Brewer’s website

Leave A Comment