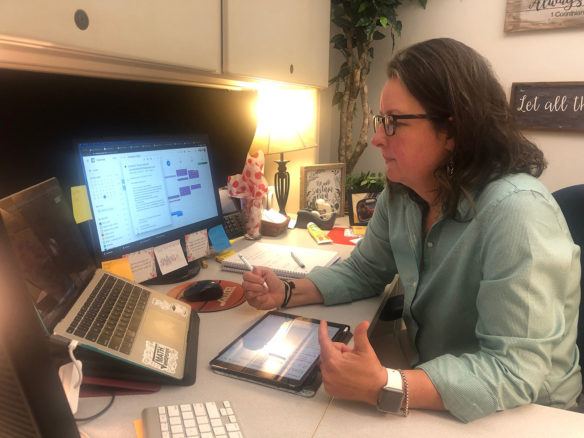

Barren Academy of Virtual and Expanded Learning (BAVEL) teacher Pam Carter conducts a fully online class. BAVEL has been holding online-only classes for 15 years. When all public schools had to move their learning online in March due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many educators began turning to the school for tips on how to make online education work.

Photo submitted

- BAVEL has developed techniques for virtual education during its 15 years of operation.

- The keys to a successful virtual education program are for a school district to know what they want it to look like and committing the time and money to make it happen.

By Jim Gaines

jim.gaines@education.ky.gov

In spring 2020, Kentucky schools and others across the country scrambled to set up online classes due to COVID-19 shutdowns. As they did, educators sought advice on how to do that successfully. Though many schools had some form of virtual program, this was their first experience with full-time remote learning.

Kentucky educators had an example: the Barren Academy of Virtual and Expanded Learning (BAVEL), which for 15 years has been doing what other Kentucky schools suddenly needed.

Marty Park, chief digital officer in the Kentucky Department of Education (KDE) Office of Education Technology, said when a dozen or more districts sought help in launching virtual programs this summer, his first move was to connect them with BAVEL.

“They’ve been doing this for a very long time and they do it very well,” he said.

BAVEL’s personnel were ready to help districts think through how to create virtual programs, said Scott Harper, who oversees BAVEL as director of instruction for Barren County Schools.

The first of KDE’s guidelines for digital learning is to ensure the content is aligned with the Kentucky Academic Standards, Park said. His office has a catalog of all virtual courses offered by various Kentucky schools, and BAVEL has the most, he said.

BAVEL was never built around helping students retake classes, rather providing a rigorous and unique education, said former Metcalfe County Superintendent Benny Lile. Even though Metcalfe County students usually decided against taking courses through BAVEL, he said checking it out often changed their perspective on education – helping them accept that there was no easy way to learn and online classes could be just as demanding as in-person instruction.

“If that’s the lesson learned, then cumulatively I think it’s all really good,” he said.

What BAVEL Can Teach

BAVEL administrators get plenty of questions from schools every year about how to operate remote learning programs, Harper said.

The first essential factor, whether for non-traditional instruction during COVID-19 or a permanent online program, is a clearly established vision for what the program should accomplish, said Phillip Napier, BAVEL’s director of communication and assessment. Other schools’ visions for online programs may be very different from BAVEL, but the important thing is for everyone involved to understand it, he said.

Next, schools must understand how they’ll facilitate student success, Napier said, such as determining the technology infrastructure they will they need and ensuring students get the right support.

Then schools need to anticipate and overcome the barriers they and their students will face, from gaps in technology to transporting students to standardized testing sites.

Some people have had bad online experiences, often because they found it impersonal, Napier said. BAVEL seeks to ensure that when its students graduate, they’ve had a chance to develop “soft skills” as well as academic ones.

BAVEL’s leaders agree that any new online program needs to “start small” to plan and prepare.

“Really, it’s all about meeting the needs of the students,” Harper said. Many of their students wouldn’t have been successful if they hadn’t had the options BAVEL’s online program provides, he said.

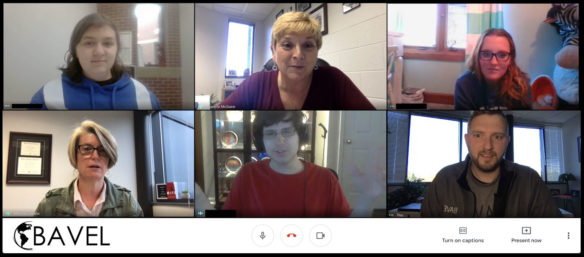

BAVEL administrators Jeanelle McGuire, (top center), Melinda Owens (bottom left) and Phillip Napier (bottom right) hold a video conference with students Gracyn Wellman (top left), Madeleine Edge (top right) and Justin Burba (bottom center).

Photo submitted

Park, who oversees all online and virtual school networks in the state, said KDE is launching expanded ideas of what that statewide virtual learning network looks like. Much of his office’s work is expanding how technology can help traditional classroom teachers in day-to-day learning, he said.

One of Kentucky’s educational gaps, however, has been providing opportunities for any student to enroll in a high-quality, all-virtual program, Park said. As the state’s longest-serving full-time virtual school, BAVEL serves as a benchmark, he said.

“We really look at them as the source of excellence for doing full-time virtual school really well,” he said. “Because of the demonstrated success of BAVEL, we’re now up to 38 school districts that have a virtual academy or virtual school approach, and they are accepting students from other districts.”

BAVEL does a great job ensuring its program is the right fit for student applicants, working closely with families, Park said.

This summer, Park and Ben Maynard in KDE’s Office of Education Technology asked BAVEL personnel to hold a professional development session for teachers in other districts. That online event took place July 16, dealing with the history of online education in Kentucky, BAVEL itself, and what its educators have learned about providing a solid virtual-only education.

Park’s office is working on using some Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act funds to help other districts host their own virtual academies, he said.

Background on BAVEL

BAVEL was established in 2004. It serves public, private and homeschool students in grades 6-12, providing standard instruction and Advanced Placement classes. It also offers dual credit classes in partnership with Kentucky colleges and universities.

Barren County School District runs and funds BAVEL, using Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Support Education Excellence in Kentucky (SEEK) funding, Harper said.

BAVEL has two full-time instructors, 46 part-time teachers, three directors and an administrative assistant, Napier said. It’s accredited through the NCAA, so its graduates who are student athletes in their home districts are eligible to play in college, he said.

More than 2,500 students have taken BAVEL courses and more than 600 have graduated through BAVEL, according to the school.

Th school serves students statewide, said Jeanelle McGuire, BAVEL’s director of admissions.

Students who enroll in BAVEL take classes under reciprocal agreements between the school and their home districts at a cost of $50 per course. But that’s a deposit refundable upon graduation, she said.

Putting down a deposit shows that students are committed to a course, Napier said. And getting it back when they graduate is “icing on the cake,” he said.

Students from districts without reciprocal agreements can take BAVEL classes, too, but in their case the per-course charge isn’t refundable and may vary depending on which classes they take and how many, Napier said.

This year, BAVEL has reciprocal agreements with 66 of the state’s 171 districts.

BAVEL values its partnerships with other school districts, universities and the state’s community and technical college system, Harper said. Barren County is one of the top feeders of students to Western Kentucky University (WKU), and last spring the university started talks with BAVEL on a closer collaboration, he said.

Aiding that potential collaboration is BAVEL’s recent move from Barren County School District offices to a building on WKU’s Glasgow campus. That will allow BAVEL to draw from WKU’s advising resources and other campus features, Napier said.

Normally, administrators and the two full-time instructors have offices in BAVEL’s campus building, while the part-time teachers work from home, he said.

When schools shut down in the spring, all BAVEL staff were able to work from home – even having their office phones physically installed in their houses, Harper said.

“We had the technology infrastructure to do that pretty seamlessly,” he said.

Growth and Change

BAVEL started in 2004 with only eight students, Napier said.

“Just a handful of our local students that needed another option for fulfilling their requirements to get their high school diploma,” he said. Providing that alternative is the reason BAVEL was founded.

When Napier began at BAVEL in 2010, the school had 75 students.

“The next school year we ended up somewhere around the 200 mark,” he said. For fall 2020, enrollment is up about 20% over 2019.

Though growth has been steady, the number of unique students fluctuates annually, Napier said.

“What really tells our story is the number of course enrollments,” he said. Fewer total students may enroll in any given year, but more of them are enrolled full time.

This year BAVEL has 292 students altogether.

Those students make up 2,768 individual enrollments, meaning individual classes, Napier said.

Usually about 85% of students are full time, but in 2020, that rose to 92%, he said.

Other virtual schools will accept students from other districts, but unless those districts have reciprocal agreements, parents have to pay out of pocket, Park said.

He wants to expand virtual networks’ footprint so more districts have reciprocal agreements with multiple partners.

“No one should expect it to be free, but there’s a funding conversation that has to take place with every district,” Park said.

Time and Technology

It took time to build BAVEL’s infrastructure and reach its current capacity, Napier said.

“It’s important to remember that we didn’t just get here overnight,” he said. “We are, even at this point, still experiencing growing pains and still learning what authentic online learning really looks like.”

One of the biggest investments is not technology, Napier said. It’s people: teachers and support staff who follow students’ progress.

“It’s really about that whole experience and knowing there are people on the other end that care,” he said.

Owens monitors students’ coursework, discussing issues with them if they fall behind and encouraging them further if they’re doing well. She seeks to make sure students really understand their curriculum and can discuss it, not just recite it.

Regular, personal contact with teachers is built into BAVEL’s curriculum, Harper said.

Much of that is enabled or assisted by the evolution of videoconferencing over the past decade, Owens said. In the early years, students had to enroll in person, then could do it by phone and now can use Google Meet from their first day.

Everyone wants the socialization benefits that come from in-person school, but learning can work very well online, Lile said.

For districts working to set up a permanent routine of virtual education, the main factor is determining up front what they want their online presence to be like, he said.

“I think one of their big things is, there’s always been a teacher behind the course,” Lile said. BAVEL classes are far more than working through and submitting assignments via computer, he said.

Leave A Comment