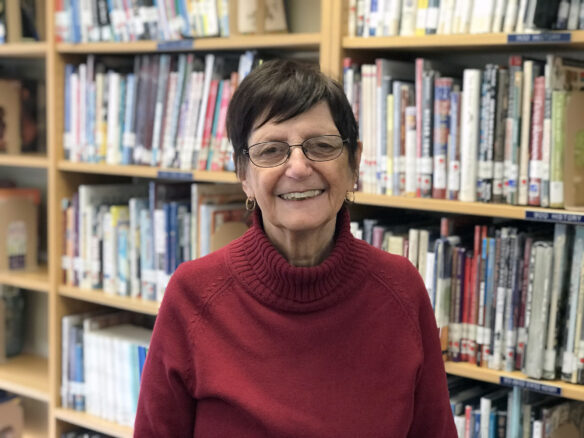

Ann Brewster retired on June 30 after nearly 60 years in education. She served as principal of Ramey-Estep High School in Boyd County for the last 20 years. Photo courtesy of Ronnie Nolan.

On June 30, Ann Brewster officially retired at age 80 from her 59-year teaching career.

“I swore I never would [become a teacher],” Brewster said. “My dad was a superintendent … my mom was a teacher and taught her whole life.”

But when she was in college, Brewster said the only feasible options for women in the workplace were as a nurse, a secretary or a teacher.

Brewster’s career began when she was just 21 years old. Over the years, she has worked in various positions from the National Ski Patrol to government, but she has always returned to teaching.

Now she proudly carries on her family’s legacy in the school system.

Most recently, she served as principal of Ramey-Estep High School (REHS) (Boyd County) for the last 20 years. REHS is a public alternative school directly connected with Ramey-Estep Homes Inc.

Ronnie Nolan, executive director of the Kentucky Educational Collaborative for State Agency Children (KECSAC), said, about 65% [of REHS students] are in the care and custody of the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services.

Nolan and Brewster met 18 years ago through Nolan’s involvement with KECSAC, and the two have remained friends and colleagues ever since.

“It was very evident from our first meeting that she is a person who has a huge heart for the student population,” said Nolan.

He is excited that Brewster’s story was being shared.

“I feel like alternative educators are often not recognized for the incredible work that they do.”

The two have collaborated on multiple projects over the years. One that stands out to both of them was Brewster’s creation: “Where the Heart Is,” a free amenity for students transitioning out of government care and back into traditional public schools.

Participating public school teachers received specialized training and then put a specific logo on the doors of their classrooms that indicate they were trained, a safe person to talk to and non-judgmental. Transitioning students saw these logos and knew they had a support system of teachers to turn to with concerns and questions.

Although the project is no longer running, Brewster continues to advocate for her students.

“I love these kids. I can see beyond their behavior … I give every student my respect,” she said.

The students who attend alternative education schools typically come from situations involving abuse, neglect and/or child endangerment. Brewster said her commitment to give every student her respect may be the first time in their lives these students have received that level of dignity from an adult.

Nolan said Brewster “wants [her students] to learn how to be successful and to learn how to manage their emotions [and] how to be able to manage their reactions to things that are happening to them.

“Things happen to them a lot, and it’s about creating those opportunities for them to make things happen and not just to have things happen to them.”

When asked if she had ever considered leaving the teaching profession early, Brewster said, “I wasn’t willing to give up being with kids full time.” She added that she would work with students forever if she could, but she has peace in knowing her family needs her now.

Brewster’s 59 years of service to public school systems in West Virginia, Florida and Kentucky have been filled with happiness, challenges and gratitude. She says her previous students still reach out to her occasionally.

“I wish incoming teachers were required to teach briefly in an alternative education environment,” she said. “It would greatly benefit their perspectives on the world and teaching in general. Those [students] who act the worst need your love the most.”

Brewster will enjoy her retirement from her home in West Virginia with her husband, children and seven grandchildren.

Wonderful article, Ann. You have been a gifted educator. I know your parents would be so proud.

How amazing