By Ashley Lamb-Sinclair

ashley.lambsinclair@oldham.kyschools.us

When I was in high school, one of my closest friend’s father was an obsessive runner. I remember thinking he was at the height of insanity when, on his 50th birthday, he chose to run 50 miles around our hometown. If anyone is wondering, when I turn 50, I intend to be on a beach somewhere lying around—pretty much the opposite of running from dawn to dusk. But he wanted to do it.

When my friend told me that her father planned to run a 10-mile loop and come back home to rest before heading out again, I thought it both insane and also kind of cheating. I mean, if you’re going to run 50 miles, run 50 miles. Don’t wimp out on the deal.

Now, however, with years since high school to think about it, I actually think he was on to something. You can run 50 miles, 10 miles at a time. And having taught for 10 years, I realize that I spent a good majority of my career with this kind of “all or nothing” mentality.

How many times did I collect every single word that my students wrote, only to recognize that I could never read and respond thoughtfully to all of it? How many times did I spend my entire weekend planning for the week ahead, only to discover that I could get as far as Monday afternoon before realizing it didn’t work and I needed to start over? How many times did I tell myself that I wasn’t doing enough — that no matter how little I slept or ate or talked to adult human beings, I was still not doing enough?

How often did I force these kinds of expectations on my students without recognizing that our brains and bodies do not work best this way? I believe this kind of thinking causes good teachers to burn out and prevents our students from getting the best of us and themselves. We all need a place to rest once in a while.

As teachers, we are guilty of putting this pressure on ourselves, often because of the pressure put on us by our culture and our educational system. We also are guilty of putting this kind of pressure on our students.

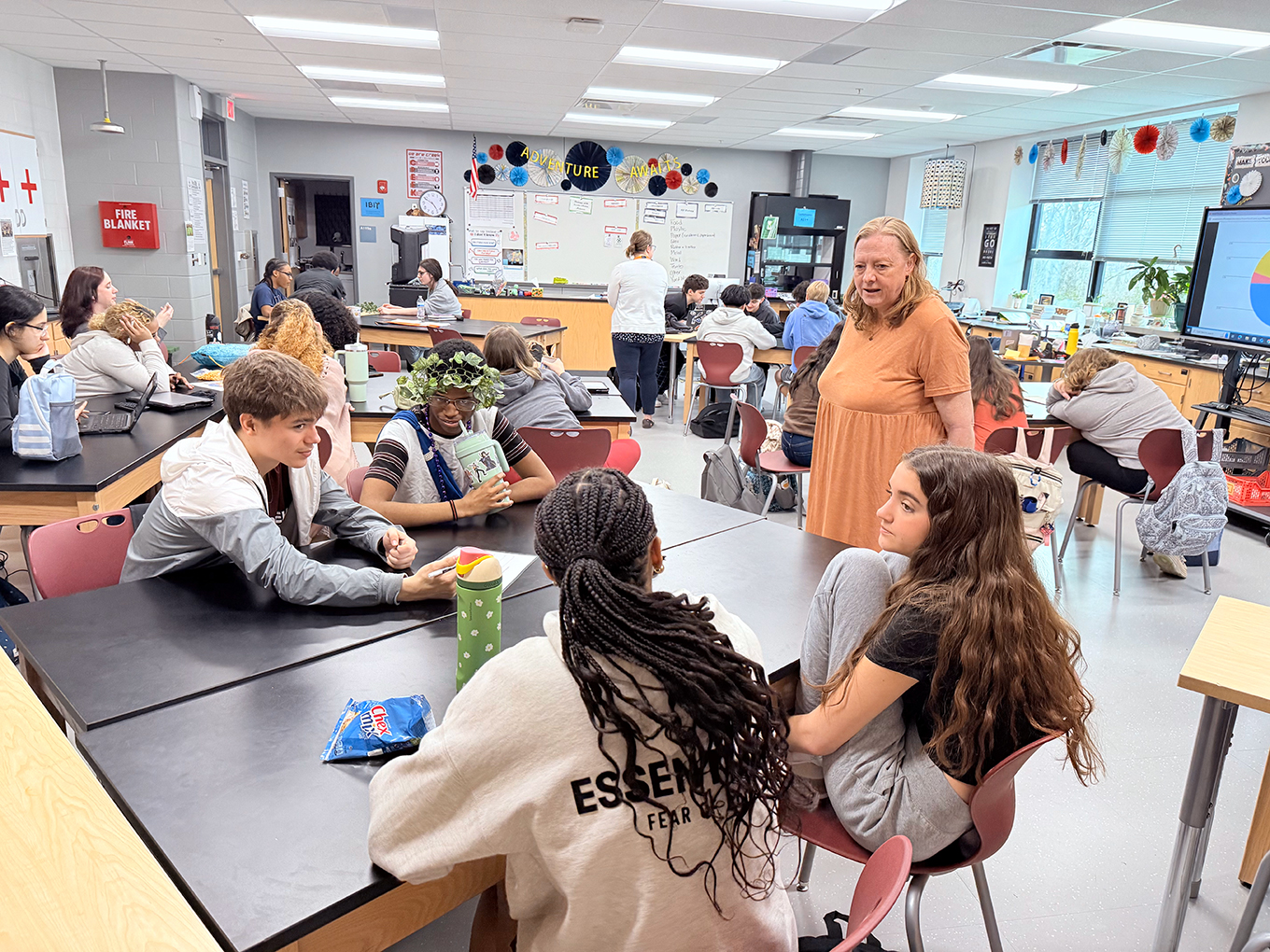

Here in Oldham County, I recently had the pleasure of observing a highly skilled humanities teacher named Melanie Kidwell. Melanie’s classroom felt the way I imagine my friend’s house must have felt during her father’s restful moments of silence, when his muscles relaxed and his breath slowed down. Her presence was calming. Her students were at ease. Everything about her classroom created a sense of peace. Kids felt safe enough to raise their hands enthusiastically, even when the question posed was a really challenging one.

Melanie was present with them. No one secretly checked their email or their text messages; no one scanned the wall for a clock to check the time. Her classroom was the kind of place where you want to prop up your feet and just sit inside for a while. Yet, it was also one of the most rigorous classrooms I’ve observed. Students asked tough questions of each other as they wrestled with analyzing and making meaning of a piece of art about Native American justice. Melanie challenged them to provide deeper answers to her questions, never letting them off the hook with just scratching the surface. Arguments inevitably arose, but Melanie didn’t let them make claims they couldn’t back up with proof.

After spending time in Melanie’s classroom, I wondered how she was able to create this environment. I can’t help but consider the fact that her subject is not tested, and by her own admission, she has been granted the professional judgment to slow down the learning that takes place in her class. Melanie’s classroom thrived as both a rigorous and restful place because she gave herself and her students the space to think. She gave them all a break from the running of their minds. They grappled with difficult material at high levels, but she never rushed them along. When she asked them to work with a partner to analyze the material and prove their inferences, she gave them time to work. She didn’t hover, pushing and prodding them to come to her conclusions. She made herself available and she helped when she could, but mostly she let them learn by doing the work themselves. She doesn’t feel the pressure of coverage and time limits the way so many other teachers do. Melanie was that silent resting spot for them as they jogged around their own ideas.

I will not put on my running shoes and attempt to run 50 miles anytime soon, if ever. But I do spend too much time running around in other ways. The next time I find myself racing at breakneck speed to do more, expect more and be more, I will try to remember Melanie Kidwell’s humanities class – a place of rest and rigor. I will remind myself to stop and give myself and my kids a little break. You can run just as far, but you run much smarter that way.

Ashley Lamb-Sinclair is the 2016 Kentucky Teacher of the Year, a National Board certified teacher and is in her 10th year of teaching. She has taught in Fayette and Jefferson counties and now teaches English and creative writing at North Oldham High School (Oldham County).

While I appreciate what was said here and I can’t agree more- the one thing to note is that her subject is not tested. She won’t have to worry about being put on a corrective action plan if her scores drop. She has no real accountability that constrains her. If I could teach the way I really want and feel is best for kids (and trust me I do as much as I can at risk of test scores dropping) then I could completely embrace the expressed sentiment in the article.

What needs to happen in education is to allow teachers to teach- to provide exploration and student choice without having to worry about stilted test scores that not only fail to measure student growth adequately but also fail to really move students forward since they are no longer in your class once results are received.

Thank you for the great reminder that we can slow down and still have high expectations.

Ashley, what a thoughtful and truthful reminder of the power of presence with students. Awesome piece!